FREEDOMWALK INGREDIENTS

This guide is a general-health document for adults 18 or over. Its aim is strictly educational. It does not constitute medical advice. Please consult a medical or health professional before you begin any exercise-, nutrition-, or supplementation-related program, or if you have questions about your health.

This guide is based on scientific studies, but individual results do vary. If you engage in any activity or take any product mentioned herein, you do so of your own free will.

If you’re reading this, you probably have joint issues that refuse to go away; you’re still looking for a solution. The first thing you should know is that you’re not alone — weird, stubborn joint pains are common.

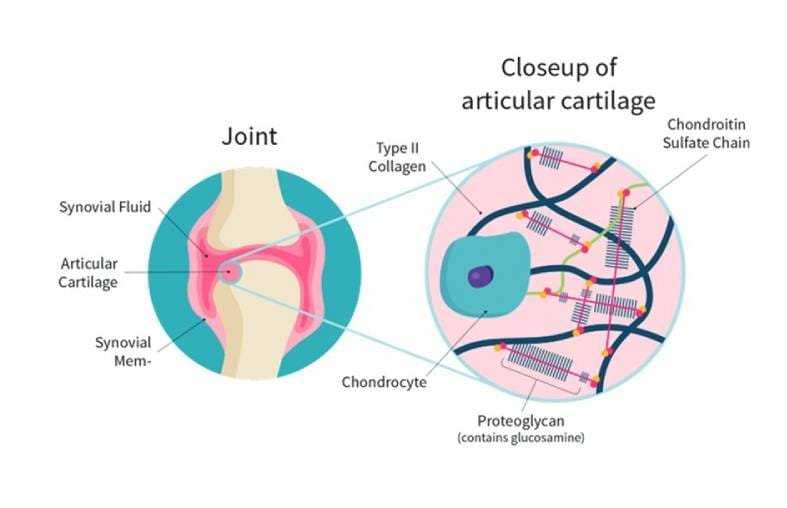

The reason joint issues are so complex is actually quite interesting. There are many ways you can damage your joints: by forcing past their range of motion (e.g., by tearing your ACL), by routinely messing up their surroundings (e.g., by letting your bad posture compress one of the shoulder joints), or through more insidious processes (e.g., wear and tear from aging or disease). The multiplicity of possible causes, which often intersect, makes addressing joint pain difficult, as does the complexity of the joint tissue itself. Here we highlight just a few components of articular cartilage:

Digging Deeper: Weird joint pain

Why do some cases of joint pain resolve quickly, whereas others worsen or stay the same? Unfortunately, that topic isn’t well understood,[1]

Try physical therapy and anti-inflammatories (e.g., NSAIDs); if neither helps, consider surgery. Such is the traditional approach to joint pain; it is simplistic and fraught with problems, of which we’ll mention only a couple:

Lasting joint pain can often be blamed on inflammatory tendonitis, and physicians may not look any further. Yet it could also be caused by non-inflammatory tendinosis [2] (if, for example, the tendon tissue has degenerated past the point of having an inflammatory response to injury).

Several joint surgeries have recently been found to be much less effective than assumed, prompting guidelines against surgery as a primary option.[3]

It’s your body, so don’t be afraid to ask a ton of questions. Weird joint pain is worth digging into, possibly through second opinions along with self-education. It may stem from a condition as common (yet complex and difficult to treat) as fibromyalgia,[4] or as rare as Fabry disease.[5]

The reason joint issues are so complex is actually quite interesting. There are many ways you can damage your joints: by forcing past their range of motion (e.g., by tearing your ACL), by routinely messing up their surroundings (e.g., by letting your bad posture compress one of the shoulder joints), or through more insidious processes (e.g., wear and tear from aging or disease). The multiplicity of possible causes, which often intersect, makes addressing joint pain difficult, as does the complexity of the joint tissue itself. Here we highlight just a few components of articular cartilage:

What is cartilage

Yet when your joints work smoothly, you don’t think about them at all. It’s only when they stop working well, and keep not working, that you can’t stop thinking about them. And that’s where much of the problem lies.

We humans, with our relatively defenseless bodies, must employ a fairly robust alarm system to warn our big brain that it is indirectly in danger (for our distant ancestors, a damaged joint could easily be a death knell). Pain is a helpful signal when it works correctly: it helps us live out our long human lifespans. It follows that, to ensure its survival, your body can become “better and better” at experiencing pain; in other words, your nervous system lowers the threshold over which signals are interpreted as painful (through varied mechanisms, notably central sensitization[6]).

Humans respond to pain so differently from most other mammals that painkillers that work in animal studies often fail in human studies.[7] In humans, we observe a pretty clear dichotomy: acute pain (from overexerting yourself at the gym, for instance) responds well to medication and other interventions. Chronic pain, sadly, does not.[8]

Freedom Walk Combo

Joint pain is caused by a variety of factors.

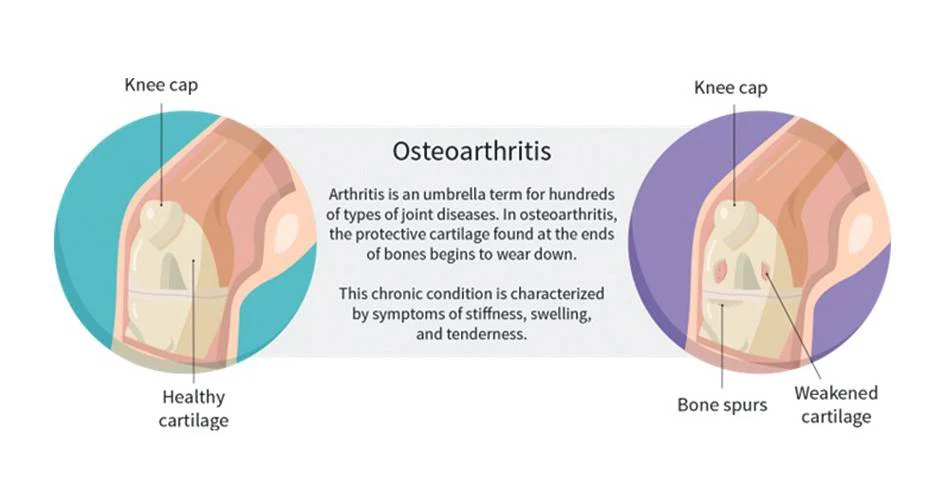

For people with osteoarthritis

Each day, with food, take Freedomwalk which is a blend of 1.2 g of chondroitin sulfate, 1.5 g of glucosamine sulfate, 100 mg of Pine bark extract, and some collagen in the form of undenatured type- II collagen (40 mg), 250mg of Boswellia serrata to your regimen

Studies on Boswellia serrata tend to use one of two patented extracts: 5-Loxin and Aflapin. We gave you the best.

Vitamin C 500mg once a day in Freedomwalk helps to reduce the risk of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

Curcumin is a component of turmeric (Curcuma longa). Its bioavailability can be greatly increased by taking it with piperine (a black pepper extract). To supplement curcumin with piperine 1.5 g of curcumin and 60 mg of piperine in Freedomwalk helps to improving knee flexibility and reduce inflammation.

Core supplements have the best safety-efficacy profile. When used responsibly, they are the supplements most likely to help and not cause side effects.

Boswellia Serrata

What makes Boswellia serrata a primary option

Boswellia serrata is a plant used medicine notably to alleviate joint pain. Research suggests that it could be as effective as some pharmaceuticals for the purpose of alleviating joint pain and improving knee flexibility in people with osteoarthritis.

What is osteoarthritis?

Boswellia serrata is often used alongside Curcuma longa (turmeric), a plant rich in curcumin.

Chondroitin

What makes chondroitin a primary option

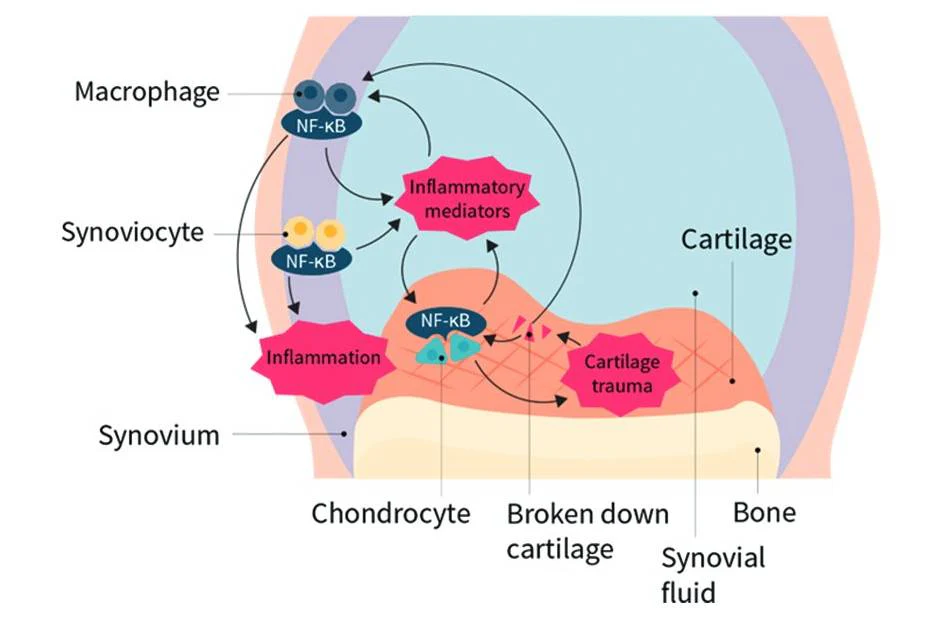

Studies on knee osteoarthritis suggest that supplementation of chondroitin (a component of cartilage) can reduce water retention in inflamed joints, improve mobility, and reduce pain.[9] Its anti-inflammatory effects[10] could be occurring through inhibition of the protein complex NF-κB,

which regulates a host of inflammatory responses.[10]

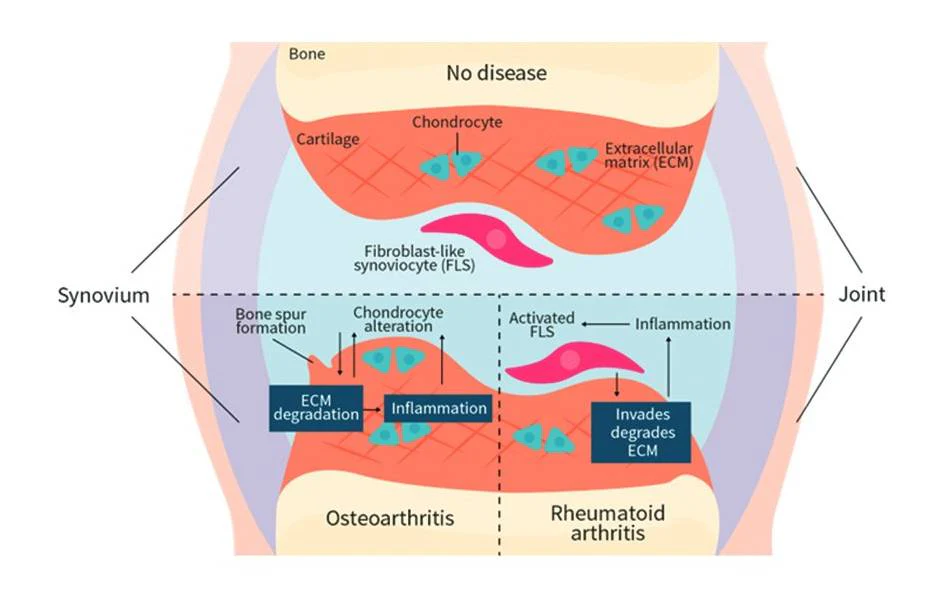

Putative inflammatory interplay between the synovium and cartilage

Adapted from Lovu et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008.[10]

Like collagen and glucosamine, chondroitin is a component of cartilage, and there is some evidence that it may reduce cartilage loss. With regard to joint pain and mobility, chondroitin and glucosamine show modest benefits in many studies; by contrast, collagen, curcumin, and Boswellia serrata show greater benefits.

Orally supplementing with chondroitin is relatively safe.[11]

While there is good evidence that suggests chondroitin could slow the progress of osteoarthritis, its efficacy is not a settled matter. Some researchers have suggested that the question of efficacy may be, in part, due to poor quality control in chondroitin supplements.[12] Some formulations of chondroitin sulfate could have dosing variations, contaminants, or composition differences. Using pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin, whose purity and dose is vetted, may be more effective.[13][14]

Collagen

What makes collagen a primary option

Collagen amounts to 25–35% of total protein in mammals, which makes it the most abundant protein in our bodies.

The collagen in joint cartilage is 80–90% type-II collagen. Current research suggests that undenatured type-II collagen (UC-II) may reduce swelling, joint pain, and stiffness in cases of moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis and both juvenile and adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis.

How cartilage degrades in osteoarthritis vs. rheumatoid arthritis

Adapted from Smolen and Aletaha. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015.[15]

As with chondroitin and glucosamine, two other components of cartilage, there is some evidence that collagen may reduce cartilage loss.

Curcumin

What makes curcumin a primary option

Curcumin is a component of turmeric (Curcuma longa). It can inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and thus reduce inflammation in the body, so its action is similar to that of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). [16]

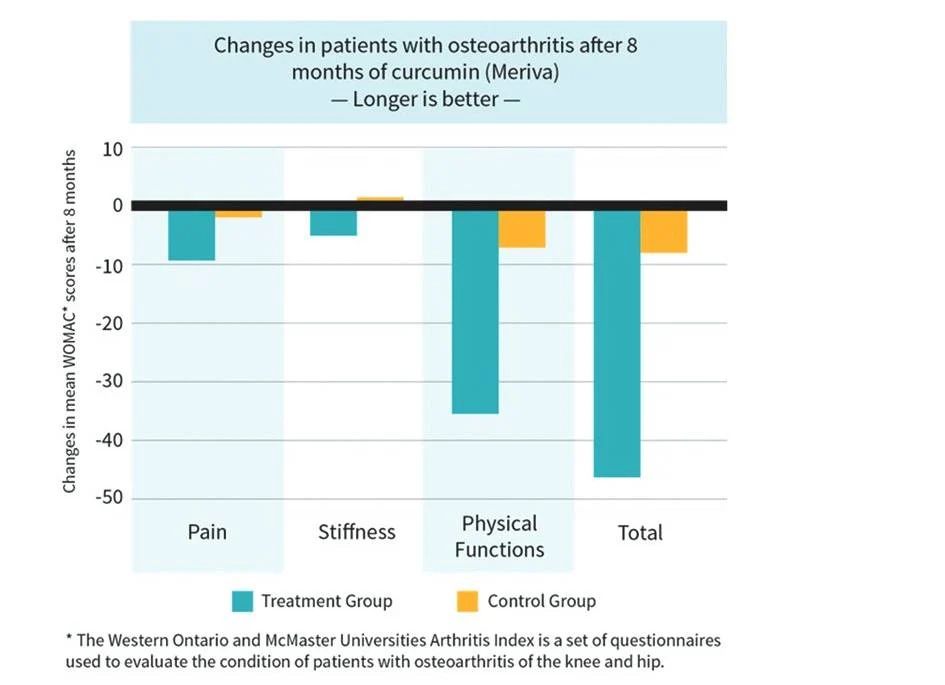

Many studies looking at the effects of curcumin and turmeric on osteoarthritis symptoms have been conducted.[17]18[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] Most of the higher-quality studies have found a positive effect on overall symptoms, particularly pain, and also physical function and the effects tends to be medium-large.

Curcumin’s effects on patients with osteoarthritis

Reference: Belcaro et al. Altern Med Rev. 2010.[18]

Some athletes use curcumin to fight muscle inflammation. In theory, curcumin should have effects similar in nature and potency to those of aspirin.Curcuma longa is often used alongside Boswellia serrata

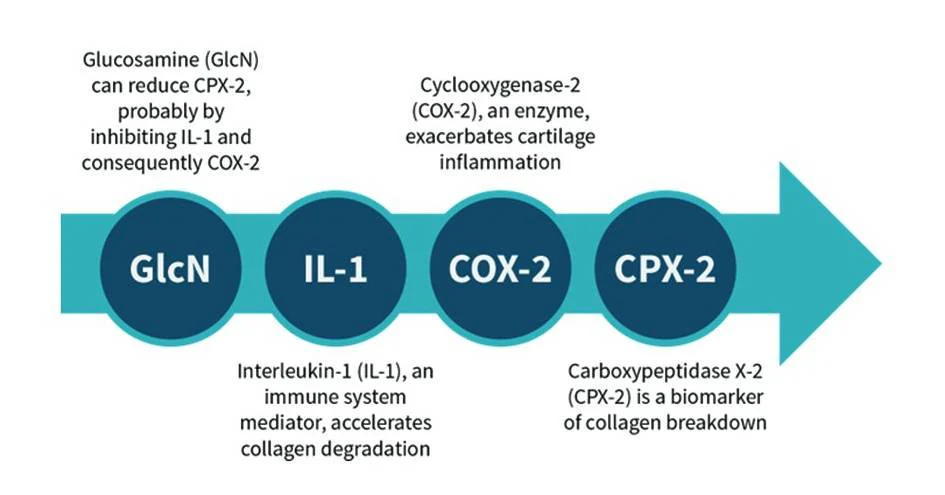

Glucosamine

What makes glucosamine a primary option

For the treatment of knee osteoarthritis, there are more trials on glucosamine (a component of cartilage) than on any other supplement. Pooled results show a reduction in pain and an improvement in function — both modest on average, but with important interindividual variability. In some people, glucosamine relieves pain as well as acetaminophen (Tylenol), a pharmaceutical painkiller. In others, alas, it has no effect. People taking glucosamine should monitor their symptoms to better assess if this supplement works for them.

Like collagen and chondroitin, glucosamine is a component of cartilage, and there is some evidence that it may reduce cartilage loss.

Glucosamine’s cartilage-preserving effects

Glucosamine sulfate sodium chloride is the best-studied form of crystalline glucosamine sulfate

Pine bark extract

The flavonoids called procyanidins can improve blood flow and reduce inflammation. Pine bark extract is a patented pine bark extract standardized to 65–75% procyanidin; there is preliminary evidence that it can benefit people with osteoarthritis, but further research is needed for confirmation.

Grape seed extracts are rich in procyanidins and cheaper than pine bark extracts, but their benefits to joint health have never been directly demonstrated so we have considered Pine bark extract in Freedom Walk.

Vitamin C

What makes vitamin C a primary option

Vitamin C is necessary for collagen formation, so having low levels of vitamin C can be detrimental to joint health. In people whose levels are normal, however, supplemental vitamin C has little effect on joint disorders, with one exception: It can help prevent complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), a painful chronic condition characterized by swollen joints.

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin C for adults ranges from 75–120 mg per day.[30] Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 2,000 mg/day.

SCIENTIFIC LINKS

- Mifflin KA, Kerr BJ. The transition from acute to chronic pain: understanding how different biological systems interact. Can J Anaesth. (2014)

- Kaeding C, Best TM. Tendinosis: pathophysiology and nonoperative treatment. Sports Health. (2009)

- Siemieniuk RAC, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline. Br J Sports Med. (2018)

- Queiroz LP. Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. (2013)

- Politei J, et al. When arthralgia is not arthritis. Eur J Rheumatol. (2016)

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. (2011)

- Joshi SK, Honore P. Animal models of pain for drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. (2006)

- Wang CK, Myunghae Hah J, Carroll I. Factors contributing to pain chronicity. Curr Pain Headache Rep. (2009)

- Singh JA, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015)

- a b c Iovu M, Dumais G, du Souich P. Anti-inflammatory activity of chondroitin sulfate. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2008)

- Fardellone P, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety study of two chondroitin sulfate preparations from different origin (avian and bovine) in symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Open Rheumatol J. (2013)

- Martel-Pelletier J, et al. Discrepancies in composition and biological effects of different formulations of chondroitin sulfate. Molecules. (2015)

- Honvo G, Bruyère O, Reginster JY. Update on the role of pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin sulfate in the symptomatic management of knee osteoarthritis. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2019)

- Pelletier JP, et al. Chondroitin sulfate efficacy versus celecoxib on knee osteoarthritis structural changes using magnetic resonance imaging: a 2-year multicentre exploratory study. Arthritis Res Ther. (2016)

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2015)

- Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin: A Review of Its’ Effects on Human Health. Foods. (2017)

- Panahi Y, et al. Curcuminoid treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. (2014)

- a b Belcaro G, et al. Efficacy and safety of Meriva®, a curcumin- phosphatidylcholine complex, during extended administration in osteoarthritis patients. Altern Med Rev. (2010)

- Belcaro G, et al. Product-evaluation registry of Meriva®, a curcumin- phosphatidylcholine complex, for the complementary management of osteoarthritis. Panminerva Med. (2010)

- Kuptniratsaikul V, et al. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. (2009)

- Madhu K, Chanda K, Saji MJ. Safety and efficacy of Curcuma longa extract in the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology. (2013)

- Nakagawa Y, et al. Short-term effects of highly-bioavailable curcumin for treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study. J Orthop Sci. (2014)

- Haroyan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of curcumin and its combination with boswellic acid in osteoarthritis: a comparative, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2018)

- Kuptniratsaikul V, et al. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. Clin Interv Aging. (2014)

- Panda SK, et al. A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled, Parallel-Group Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Curene® versus Placebo in Reducing Symptoms of Knee OA. Biomed Res Int. (2018)

- Pinsornsak P, Niempoog S. The efficacy of Curcuma Longa L. extract as an adjuvant therapy in primary knee osteoarthritis: a randomized control trial. J Med Assoc Thai. (2012)

- Shep D, et al. Safety and efficacy of curcumin versus diclofenac in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized open-label parallel-arm study. Trials. (2019)

- Srivastava S, et al. Curcuma longa extract reduces inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in osteoarthritis of knee: a four-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology. (2016)

- Henrotin Y, et al. Bio-optimized Curcuma longa extract is efficient on knee osteoarthritis pain: a double-blind multicenter randomized placebo controlled three- arm study. Arthritis Res Ther. (2019)

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids.

Safe And Scientific

Scientifically proven ingredients

Not just claims. Scientifically proven and evidence based ingredients

Team you can trust

Products developed by a team of Nutritionists, doctors, Exercise specialists and Scientists

Take home the science

we are the first company in India giving a printed material with scientific evidence

Guide to Fit and Healthy Lifestyle

Your true partner in health & wellness